Frequently Asked Questions

How effective is the flu shot?

How effective is the flu shot?

The ability of a flu vaccine to protect a person depends on the age and health status of the person getting the vaccine, and the similarity or “match” between the viruses or virus in the vaccine and those in circulation. For more information, see Vaccine Effectiveness – How well does the Flu Vaccine Work.What are the risks from getting a flu shot?

You cannot get the flu from a flu shot. The risk of a flu shot causing serious harm or death is extremely small. However, a vaccine, like any medicine, may rarely cause serious problems, such as severe allergic reactions. Almost all people who get influenza vaccine have no serious problems from it.Seasonal Influenza Q&A

What is seasonal influenza (flu)?

Seasonal influenza, commonly called “the flu,” is caused by influenza viruses, which infect the respiratory tract (i.e., the nose, throat, lungs). Unlike many other viral respiratory infections, such as the common cold, the flu can cause severe illness and life-threatening complications in many people. It is estimated that in the United States, each year on average 5% to 20% of the population gets the flu and more than 200,000 people are hospitalized from seasonal flu-related complications. Flu seasons are unpredictable and can be severe. Over a period of 30 years, between 1976 and 2006, estimates of flu-associated deaths in the United States range from a low of about 3,000 to a high of about 49,000 people. Some people, such as older people, young children, pregnant women, and people with certain health conditions, are at high risk for serious flu complications. The best way to prevent seasonal flu is by getting a flu vaccination each year. Flu vaccines protect against the influenza viruses that research indicates will be most common during the upcoming season. Everyone 6 months and older should get vaccinated against the flu every year. Get vaccinated soon after vaccine becomes available in your community, ideally by October. Immunity sets in about two weeks after vaccination.What are the symptoms of the flu?

The flu can cause mild to severe illness, and at times can lead to death. The flu is different from a cold. The flu usually comes on suddenly. For information about flu symptoms, see Flu Symptoms & Severity.When is the flu season in the United States?

In the United States, flu season occurs in the fall and winter. The peak of flu season has occurred anywhere from late November through March. The overall health impact (e.g., infections, hospitalizations, and deaths) of a flu season varies from year to year. CDC monitors circulating flu viruses and their related disease activity and provides influenza reports (called “FluView”) each week from October through May. See Weekly U.S. Influenza Summary Update.How does CDC monitor the progress of the flu season?

CDC collects data year-round and reports on influenza (flu) activity in the United States each week from October through May. The U.S. influenza surveillance system consists of five separate categories.- Laboratory-based viral surveillance, which tracks the number and percentage of influenza-positive tests from laboratories across the country, and monitors for human infections with influenza A viruses that are different from currently circulating human influenza H1 and H3 viruses;

- Outpatient physician surveillance for influenza-like illness (ILI), which tracks the percentage of doctor visits for flu-like symptoms;

- Mortality surveillance as reported through the 122 Cities Mortality Reporting System, which tracks the percentage of deaths reported to be caused by pneumonia and influenza in 122 cities in the United States; and influenza-associated pediatric mortality as reported through the Nationally Notifiable Disease Surveillance System, which tracks the number of deaths in children with laboratory confirmed influenza infection;

- Hospitalization surveillance, which tracks laboratory confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations in children and adults through the Influenza Hospitalization Network (FluSurv-NET) and Aggregate Hospitalization and Death Reporting Activity (AHDRA); and

- State and territorial epidemiologist reports of influenza activity, which indicates the number of states affected by flu and the degree to which they are affected.

Why is there a week-long lag between the data and when it’s reported?

The influenza surveillance system is one of the largest and most timely surveillance systems at CDC. The system consists of 5 complementary surveillance categories. These categories include reports from more than 145 laboratories, about 3,000 outpatient health care providers, vital statistics offices in 122 cities, research and health care personnel at the Emerging Infections Program (EIP) sites, and influenza surveillance coordinators and state epidemiologists from all 50 state health departments and the New York City and District of Columbia health departments. Influenza surveillance data collection is based on a reporting week that starts on Sunday and ends on Saturday of each week. Each surveillance participant is requested to summarize weekly data and submit it to CDC by Tuesday afternoon of the following week. The data are then downloaded, compiled, and analyzed at CDC each Wednesday. The compiled data are interpreted and checked for anomalies which are resolved before the report is written and submitted for clearance at CDC. On Friday the report is approved, distributed, and posted on the Internet.How does the flu spread?

The main way that influenza viruses are thought to spread is from person to person in respiratory droplets of coughs and sneezes. For more information about flu transmission, visit How Flu Spreads.If I got the flu or the flu vaccine last year, will I have immunity against the flu this year?

Not necessarily. Several studies conducted over different flu seasons and involving different influenza viruses and types of flu vaccine have shown that a person’s protective antibody against influenza viruses declines over the course of a year after vaccination and infection, particularly in the elderly. So, a flu shot given during one season, or an infection acquired during one season, may not provide adequate protection through later seasons. The decline in protective antibody against the flu that occurs after vaccination or after flu infection may be influenced by several factors, including a person’s age, the antigen used in the vaccine, and the person’s health situation (for example, chronic health conditions that weaken the immune system may have an impact). This decline in protective antibody has the potential to leave some people more vulnerable to infection, illness and possibly serious complications from the same influenza viruses a year after being vaccinated or infected. So, for optimal protection against influenza, annual vaccination is recommended regardless of past vaccination status or flu infection.Does the flu have complications?

Yes. Some of the complications caused by flu include bacterial pneumonia, dehydration, and worsening of chronic medical conditions, such as congestive heart failure, asthma, or diabetes. Children may get sinus problems and ear infections as complications from the flu. For more information, see Flu Symptoms & Severity.How do I find out if I have the flu?

It is very difficult to distinguish the flu from other viral or bacterial causes of respiratory illnesses on the basis of symptoms alone. There are tests available to diagnose flu. For more information, see Diagnosing Flu.Do other respiratory viruses circulate during flu season?

In addition to flu viruses, several other respiratory viruses also can circulate during flu season and can cause symptoms and illness similar to those seen with flu infection. These non-flu viruses include rhinovirus (one cause of the “common cold”) and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).How soon will I get sick if I am exposed to the flu?

The time from when a person is exposed to flu virus to when symptoms begin is about 1 to 4 days, with an average of about 2 days.How long is a person with flu virus contagious?

Information about how long a person is contagious is available at How Flu Spreads.How many people get sick or die from the flu every year?

Flu seasons vary in severity. It is estimated that between 5% to 20% of U.S. residents get the flu, and it is estimated that more than 200,000 people are hospitalized on average for flu-related complications each year. Over a period of 30 years, between 1976 and 2006, estimates of flu-associated deaths in the United States range from a low of about 3,000 to a high of about 49,000 people.Can the flu be treated?

Yes. There are influenza antiviral drugs that can be used to treat flu illness.Is the “stomach flu” really the flu?

Many people use the term “stomach flu” to describe illnesses with nausea, vomiting or diarrhea. These symptoms can be caused by many different viruses, bacteria or even parasites. While vomiting, diarrhea, and being nauseous or “sick to your stomach” can sometimes be related to the flu — more commonly in children than adults — these problems are rarely the main symptoms of influenza. The flu is a respiratory disease and not a stomach or intestinal disease.What are the common questions parents ask about infant immunizations?

Infant Immunizations FAQs

Color version for office printing ![]() [274 KB, 2 pages]

[274 KB, 2 pages]

Q: Are vaccines safe?

A: Yes. Vaccines are very safe. The United States’ long-standing vaccine safety system ensures that vaccines are as safe as possible. Currently, the United States has the safest, most effective vaccine supply in its history. Millions of children are safely vaccinated each year. The most common side effects are typically very mild, such as pain or swelling at the injection site.

Q: What are the side effects of the vaccines? How do I treat them?

Q: What are the risks and benefits of vaccines?

A: Vaccines can prevent infectious diseases that once killed or harmed many infants, children, and adults. Without vaccines, your child is at risk for getting seriously ill and suffering pain, disability, and even death from diseases like measles and whooping cough. The main risks associated with getting vaccines are side effects, which are almost always mild (redness and swelling at the injection site) and go away within a few days. Serious side effects following vaccination, such as severe allergic reaction, are very rare and doctors and clinic staff are trained to deal with them. The disease-prevention benefits of getting vaccines are much greater than the possible side effects for almost all children.

Q: Is there a link between vaccines and autism?

Q: Can vaccines overload my baby’s immune system?

Q: Why are so many doses needed for each vaccine?

A: Getting every recommended dose of each vaccine provides your child with the best protection possible.Depending on the vaccine, more than one dose is needed to build high enough immunity to prevent disease, boost immunity that fades over time, make sure people who did not get immunity from a first dose are protected, or protect against germs that change over time, like flu. Every dose of a vaccine is important because they all protect against infectious diseases that are threats today and can be especially serious for infants and very young children.

Q: Why do vaccines start so early?

A: The recommended schedule is designed to protect infants and children by providing immunity early in life, before they are exposed to life-threatening diseases. Children are immunized early because they are susceptible to diseases at a young age, and the consequences of these diseases can be very serious, and even life-threatening, for infants and young children.

Q: What do you think of delaying some vaccines or following an alternative schedule?

A: Children do not receive any known benefits from following schedules that delay vaccines. Infants and young children who follow immunization schedules that spread out shots–or leave out shots–are at risk of developing diseases during the time that shots are delayed. Some vaccine-preventable diseases remain common in the United States, and children may be exposed to these diseases during the time they are not protected by vaccines, placing them at risk for a serious case of the disease that might cause hospitalization or death.

Q: Haven't we gotten rid of most of these diseases in this country?

A: Some vaccine-preventable diseases, like pertussis (whooping cough) and chickenpox, remain common in the United States. On the other hand, other diseases prevented by vaccines are no longer common in this country because of vaccines. However, if we stopped vaccinating, even the few cases we have in the United States could very quickly become tens or hundreds of thousands of cases. Even though many serious vaccine-preventable diseases are uncommon in the United States, some are common in other parts of the world. Even if your family does not travel internationally, you could come into contact with international travelers anywhere in your community. Kids that are not fully vaccinated and are exposed to a disease can become seriously sick and spread it through a community.

Q: What are combination vaccines? Why are they used?

Q: Can't I just wait until my child goes to school to catch up on immunizations?

A: Before entering school, young children can be exposed to vaccine-preventable diseases from parents and other adults, brothers and sisters, on a plane, at child care, or even at the grocery store. Children under age 5 are especially susceptible to diseases because their immune systems have not built up the necessary defenses to fight infection. Don’t wait to protect your baby and risk getting these diseases when he or she needs protection now.

Q: Why does my child need a chickenpox shot? Isn’t it a mild disease?

Q: My child is sick right now. Is it okay for her to still get shots?

A: Talk with the doctor, but children can usually get vaccinated even if they have a mild illness like a cold, earache, mild fever, or diarrhea. If the doctor says it is okay, your child can still get vaccinated.

Q: What are the ingredients in vaccines and what do they do?

A: Vaccines contain ingredients that cause the body to develop immunity. Vaccines also contain very small amounts of other ingredients—all of which play necessary roles either in making the vaccine, or in ensuring that the final product is safe and effective.

Q: Don't infants have natural immunity? Isn't natural immunity better than the kind from vaccines?

What are vaccines?

What are vaccines? "Vaccines help our bodies make protection against life-threatening infectious diseases," says Anne Schuchat, MD, director of the CDC's National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases.

When a germ invades the body, the immune system recognizes it as a foreign invader. This sets off a cascade of events. The immune system makes antibodies, which are specialized molecules that stick to the invader and either inactivate it or mark it for destruction. Specialized immune cells also seek out and destroy germs and cells in which germs are multiplying. Other immune cells remember the germ so the next time a germ of the same kind tries to invade the body, the immune system will be able to mount an immediate response. Vaccines offer a shortcut to immunity by raising protective immune responses before a germ invades. This gives the body a crucial head start that lets it prevent dangerous infections or make them less severe.What is the flu shot?

What is the flu shot?

The flu shot is a vaccine given with a needle, usually in the arm. The seasonal flu shot protects against the three or four influenza viruses that research indicates will be most common during the upcoming season.Is there more than one type of flu shot available?

- Standard-dose trivalent shots (IIV3) that are manufactured using virus grown in eggs. Different flu shots are approved for people of different ages, but there are flu shots that are approved for use in people as young as 6 months of age and up. (Most flu shots are given with a needle. One flu vaccine also can be given with a jet injector, for persons aged 18 through 64 years.)

- An intradermal trivalent shot, which is injected into the skin instead of the muscle and uses a much smaller needle than the regular flu shot. It is approved for people 18 through 64 years of age.

- A high-dose trivalent shot, approved for people 65 and older.

- A trivalent shot containing virus grown in cell culture, which is approved for people 18 and older.

- A recombinant trivalent shot that is egg-free, approved for people 18 years and older.

- A quadrivalent flu shot.

- A quadrivalent nasal spray vaccine, approved for people 2 through 49 years of age (recommended preferentially for healthy* children 2 years through 8 years old when immediately available and there are no contraindications or precautions).

What vaccines do children need?

Please review this paper Recommended Immunizations for Preteens and Teens (7-18 years)2015 Recommended ImmunizationsWhat Would Happen If We Stopped Vaccinations?

What Would Happen If We Stopped Vaccinations?

Before the middle of the last century, diseases like whooping cough, polio, measles, Haemophilus influenzae, and rubella struck hundreds of thousands of infants, children and adults in the U.S.. Thousands died every year from them. As vaccines were developed and became widely used, rates of these diseases declined until today most of them are nearly gone from our country.- Nearly everyone in the U.S. got measles before there was a vaccine, and hundreds died from it each year. Today, most doctors have never seen a case of measles.

- More than 15,000 Americans died from diphtheria in 1921, before there was a vaccine. Only one case of diphtheria has been reported to CDC since 2004.

- An epidemic of rubella (German measles) in 1964-65 infected 12½ million Americans, killed 2,000 babies, and caused 11,000 miscarriages. In 2012, 9 cases of rubella were reported to CDC.

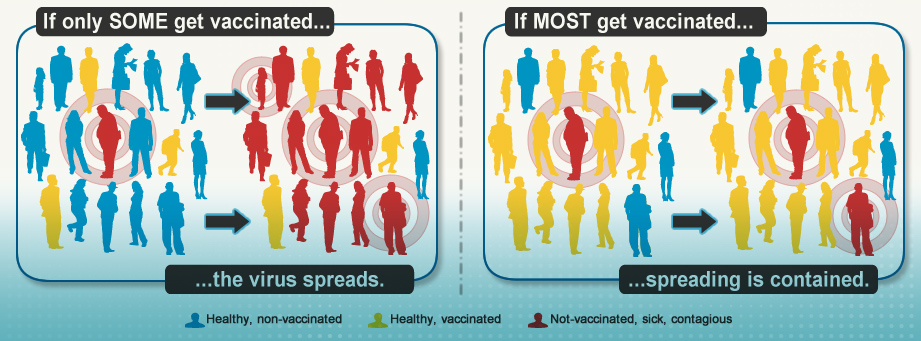

Vaccines don’t just protect yourself.

Most vaccine-preventable diseases are spread from person to person. If one person in a community gets an infectious disease, he can spread it to others who are not immune. But a person who is immune to a disease because she has been vaccinated can’t get that disease and can’t spread it to others. The more people who are vaccinated, the fewer opportunities a disease has to spread.

Diseases haven’t disappeared.

The United States has very low rates of vaccine-preventable diseases, but this isn’t true everywhere in the world. Only one disease — smallpox — has been totally erased from the planet. Polio no longer occurs in the U.S., but it is still paralyzing children in several African countries. More than 350,000 cases of measles were reported from around the world in 2011, with outbreaks in the Pacific, Asia, Africa, and Europe. In that same year, 90% of measles cases in the U.S. were associated with cases imported from another country. Only the fact that most Americans are vaccinated against measles prevented these clusters of cases from becoming epidemics. Disease rates are low in the United States today. But if we let ourselves become vulnerable by not vaccinating, a case that could touch off an outbreak of some disease that is currently under control is just a plane ride away.

Disease rates are low in the United States today. But if we let ourselves become vulnerable by not vaccinating, a case that could touch off an outbreak of some disease that is currently under control is just a plane ride away.